Nothing can stop Denise Lever. Not a raging wildfire and certainly not a state fire marshal’s effort to shut down her tutoring center by trying to impose regulations that could have forced her to spend $70,000 on building upgrades.

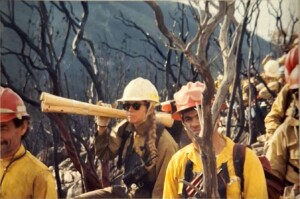

As one of the nation’s few female wildland firefighters in the late 1980s, Lever survived the hazing that came with being a woman in a male-dominated profession by proving herself and never backing down.

For example, take this story: Lever’s team had been dispatched to a California fire. Roads were closed, and the crew had to climb up a cliff to get into position. Loaded down with their gear, they pulled together and worked through the night.

“It was absolutely brutal,” Lever recalled. “It was hot. It was windy. Our hands were cut up from moving brush, and we lost gloves in the middle of the night, and we couldn’t find them on the fire line because of the debris.

As morning broke and a cold Pacific Ocean breeze stung their faces, the team huddled together in space blankets and reflected on their victory.

“The camaraderie and the sense of accomplishment, they’re irreplaceable,” Lever said.

Lever’s days of battling blazes ended when she got married and became a homeschool mom to three kids, but her trailblazing spirit stayed with her when she became an education entrepreneur.

In 2020, she opened Baker Creek Academy, a tutoring center/microschool to support homeschool families in Eagar, Arizona, just west of the New Mexico state line. The center operates four days a week for five hours per day and serves about 50 students, who attend on different days at various times. Baker Creek provides a host of supplemental services, primarily to homeschooled students, from one-on-one tutoring to limited classroom instruction and group projects to field trips. Students and parents can customize the services that best fit their needs. Baker Creek doesn’t keep attendance records because, Lever said, parents are the ones in charge.

After completing her city’s approval process, Baker Creek began operating in a historic commercial building once occupied by a church, shared with three other independent microschools.

One day, out of the blue, an official at the Arizona Office of the State Fire Marshal left Lever a voice mail message. He wanted to inspect her “school.”

“And I said, ‘No, not really, because we’re not a school,’” she said.

As an experienced firefighter, Lever recognized a school designation for what it was: the potential kiss of death for her tutoring center.

Being labeled a school triggers a list of code restrictions intended for campuses that serve hundreds or sometimes thousands of students and often include sports fields, playgrounds, auditoriums, cafeterias, gymnasiums, classrooms, and offices.

On the line are often tens of thousands of dollars in mandated building changes, which are not required for other commercial buildings, such as dance studios and karate dojos.

Levers wasted no time. She contacted the Stand Together Edupreneur Resource Center, which offers guidance, but not legal advice, about regulatory issues. The representative encouraged Lever to contact the Institute for Justice, a national public interest law firm that specializes in education choice litigation and zoning issues.

IJ Senior Attorney Erica Smith Ewing sent a letter to the state’s fire inspector questioning the basis for the inspection.

“Ms. Lever successfully completed a local fire safety inspection in 2023 and has been operating successfully with no problems,” the letter said. “Your request to inspect her property was unexpected. Could you please explain why you wish to inspect her property? We do not currently represent Ms. Lever, and we hope that formal representation will be unnecessary.”

Lever said she faced the possibility of having to spend tens of thousands of dollars upgrading doors and electrical systems. Because the building was smaller than 10,000 square feet, she avoided the order to install a sprinkler system, which can cost $100,000.

However, the timing couldn’t have been worse.

“If the state was going to require some of these upgrades, that was just not going to be possible for (our landlord) to renew our lease,” she said, adding that she used the building to host summer programs and annual meetings for other microschool leaders who use her consulting services.

Lever also wondered why similar businesses weren’t targeted — for example, a dance studio across the street that taught school-age students and operated similar hours to Baker Creek.

“Because she offered dance instead of math tutoring, her program was considered a trade, and our program was going to be shut down and treated like an education facility simply because we offered more of an academic program,” Lever said.

State officials performed the inspection, but finally backed down, offering only that the situation was a result of “confusion” and the Lever’s business wasn’t under their jurisdiction.

“Forcing Denise to follow regulations designed for sprawling, traditional schools would be both arbitrary and unconstitutional,” Ewing said. “More and more, we are seeing state and local governments hampering small, innovative microschools by forcing them into fire, zoning, and building regulations that never anticipated microschools and that make no sense being applied to what microschools do.”

In Georgia, local officials tried to force a microschool to comply with unnecessary inspections and building upgrades, in violation of state law protecting microschools. They backed down after a letter from IJ. And in Sarasota, Florida, Alison Rini, founder of Star Lab, nearly closed her doors this spring when the city interpreted the fire code to require she install a $100,000 fire sprinkler system, despite operating from a one-room building with multiple exits. Only after a donor provided a generous gift was she able to stay open.

“Teachers shouldn’t need lawyers to teach,” said IJ Attorney Mike Greenberg. “Bureaucrats shouldn’t use outdated and ill-fitting regulations to stifle parents and students from choosing the innovative education options that best suit their needs.”

Lever said the state’s decision to back off sets a precedent that will help other microschools across Arizona.

“I was definitely willing to go forth with the lawsuit,” she said. “At this point, though, we’re going to take our win. We’re going to publicize it so the other microschools will know what their options are.”